I want to follow up on the topic of treasures from the last post. This time, though, it’s not about progression but purely about storytelling and worldbuilding.

Some time ago, I pointed out how some Forbidden Lands’ themes seem to me to resemble those of the classic Wild West movies: the rough frontier, moral dilemmas, and a pull towards the anti-hero archetype that the player-characters often seem to take there. I might not be a big Western fan (though some films are great), but those themes really resonate with me when it comes to RPGs.

Inspired by my playthrough of the Hollows arc, I started piecing together a whole campaign following the convention. Though I don’t know many titles, some just started to pop into my head, and so I started writing. But I hit a serious stop soon. And that led me to one thing I needed for my creative process to kick in.

I needed names for the currency

You might not know the title of the so-called “Dollars Trilogy” featuring Clint Eastwood, but you most probably do know movie titles – or at least some of them. Those are “A Fistful of Dollars”, “For a Few Dollars More”, and “The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly”. And you’re even more likely to know their iconic soundtrack by Ennio Morricone. Why am I mentioning it?

You see, there’s a big deal in the western films’ naming convention about them dollars, right? Well, the phrase “silver pieces” just doesn’t have the same ring to it. And that ring was exactly what my imagination needed to go full-on on the Old West theme. That’s just how those creative neurons act sometimes – weird, but what can you do?

That’s why I switched gears from campaign outlining to world-building.

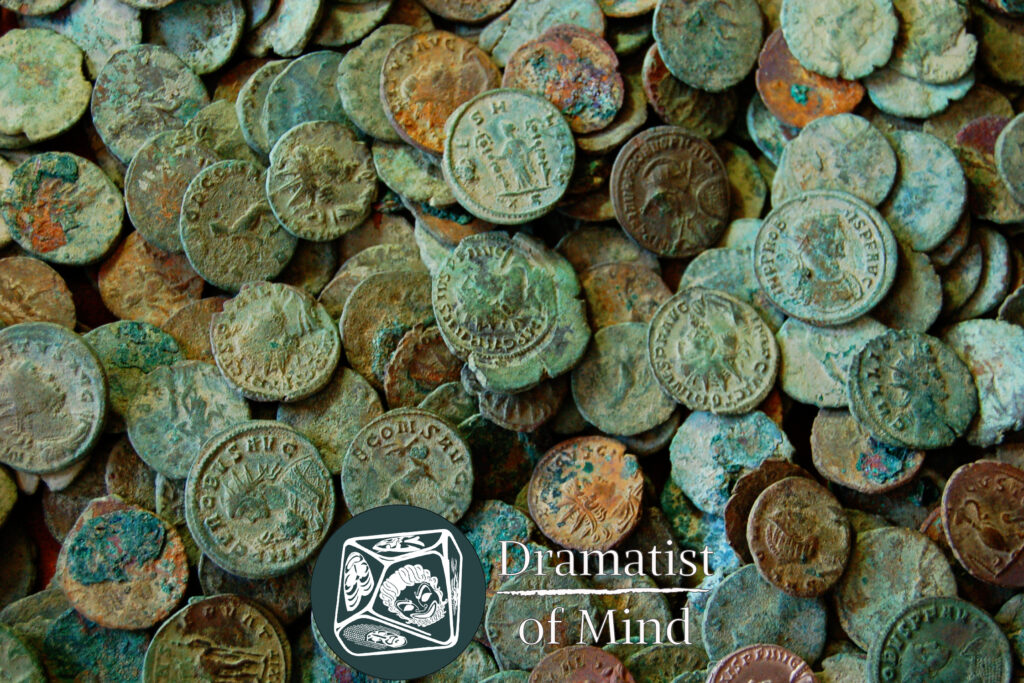

Coins add more realism to the world

I’m not saying you’ve got to do it for every game or campaign. It’s just a little detail you drop occasionally in your narration. Instead of speaking about game terms, you reference the coins by their in-world names. It’s just like having an in-game calendar, like the one that’s provided for the Forbidden Lands. Unless you’re playing a real-world game (like Call of Cthulhu or World of Darkness), using the real month or weekday names breaks the immersion.

I remember how cool it sounded when Morrowind (and probably the later Elder Scrolls games, too) referred to the money as “Septims” or “Drakes”. It just made the dialogue sound more natural. And those games also have an in-game calendar. All that sums up to a more realistic and engaging world.

How to do that efficiently?

Adding verisimilitude with ease

Let’s get practical. You don’t want to have your players memorize in-game names. Chances are, they wouldn’t even if you made them. But that’s just a bad idea. Players need clarity. So, “copper”, “silver”, and “gold” should remain as they are on the character sheet. The coinage names should be present in your narration, though.

It’s really simple: When you’re describing objects in the world where the characters can perceive them, you can mix the game terms (e.g., “silver/gold pieces”) with the in-world ones (as those I list just below). In fact, every time you use the latter, you should pair it with an explanation.

When you’re speaking about the mechanics (like an item’s value), you should use just the game terms. For example:

The chest is full of coins bearing the old Alderlander marks. You see copper snogs, silver atters, and golden nagas. It’s hard to tell how much it’s all worth exactly, but it might amount to hundred gold pieces or even more.

The players will follow

If your players are anything like my groups, they (at least some of them) will catch that on. When they’re talking in character, they’ll ask you what the name is for this or that coin. They’ll enjoy the immersion. And it will cost you next to nothing.

But let’s put the discussion aside and let me give you a short overview of what I’ve come up with.

Three coin systems for Forbidden Lands

Alderland Coins

The coins of Alderland were traditionally minted with an image of a serpent, referring to the Wyrm god. On each denomination, a different species was depicted, reflecting the natural coloring of grass snakes (green and brown), vipers (silvery hues), and cobras (creamy white, yellow-brown). On the reverse, there were minted names of the ruling Alderlander monarchs that issued the coin.

In the later years, after domination by the Church of Rust, all coins were smelted and minted anew, bearing the faces of Heme (copper coins), Rust (silver ones), and both (golden). Though the official names were also changed by a royal decree, the common people still refer to the serpentine convention unless dealing with officials or the hierarchy, in which cases those avert to the cult of Rust tend to speak of “small/great copper/silver/gold coins”.

- 1 copper – Snog (“grass snake”) / splinter

- 5 copper – Storsnog (“great grass snake”) / stake

- 1 silver – Atter (“viper”) / nail

- 5 silver – Korsatter (“crossed viper”) / hook

- 1 gold – Naja (“cobra”) / padlock

- 5 gold – Naga (“royal cobra”) / scepter

Dwarven Coins

Dwarven coins have two purposes: trade and clan- and family-identity, just like among humans. But unlike humans, dwarves had put a lot of thought into designing and refining their tools. Thus, their coins follow the base-of-two value increments1. This is to allow high granularity and precise transactions at any level. Also, the coins follow geometrical patterns for the convenience of treasurers of dwarven clans and noble houses. For the same reason, the coins have a hole punched slightly off their center for carrying known values strung on a wire. All coins bear the coat-of-arms of the clan that minted them on the obverse and the contemporary clan’s leader’s name on the reverse.

- 1 copper – støv/dust – round and simple, about ⅕ inch

- 2 copper – gryn/grain – lens-shaped (with two rounded sides meeting at two pointy ends, biconvex), half-inch long

- 4 copper – grus/gravel – square, half-inch sides

- 8 copper – sten/stone – octagon, an inch across

- 1.5 silver – filspån/filing – triangle, ¾ inch on each side

- 3 silver – klump/clod – pentagon, ¾ inch across

- 6 silver – malm/ore – heptagon, an inch across

- 1 gold – guldklimp/nugget – a triangle with a cut top corner (trapezoid), ¾ inch on each side

- 2.5 gold – block/slab – diamond-shaped (rhomb), 1 inch on each side

- 5 gold – ven/vein – thick rectangle, 1×2 inches

1 ―Rounded down to the nearest half for ease of use.

Elvish Coins

Elven artisans take their time to refine and meticulously finish each piece of their craft. It’s no different when it comes to coins. Those are usually fashioned after natural images of plant parts.

Elves use 1’s-and-12’s-based system that they allegedly keep unchanged for millennia. Curiously, the silver coins have the most variants, possibly thanks to the most opportunities for showing the craftsmen’s finesse. A large variety of shapes and sizes of flowers (as the elvish silver coins are collectively called) seemed to inspire a similar variety of such coins.

- 1 copper – Leaf – Usually triangular or tear-shaped and the size of a thumb, the elven Leaves portray their natural counterparts with striking detail. Some are even curled a bit and are known for their melodic clink.

- 3-9 copper – Broadleaf – Somewhat rarer than other copper coins, Broadleaves present a more deliberately cut outline, resembling the compound leaves of clover, maple, or chestnut. The exact value depends on the number of leaflets making up the coin. Often kept as memorabilia, token gifts or reminders of lucky events, from which probably came the human belief of the four-leaf clover bringing good luck.

- 12 copper – Twig – Around 2 inches long, Twigs are shaped like an hourglass (or biconcave, as an artisan would have it). Together with Petals, they are the most commonly used as the day-to-day currency.

- 1 silver – Petal – Oval or heart-shaped, one inch long and much thinner across.

- 12 silver – Blossom – Hexagonal in shape and an inch wide, the range of these coins is as wide as the variety of the flowering plants. Each coin seems to be a unique piece of art, and some with a taste for intricate artifacts collect those, valuing them way above their actual trade rate.

- 24 silver – Bloom – Usually octagonal, less often decagonal, Blooms depict compound flowers of elder, ivy, lilac, rowan, or lily-of-the-valley. Their value, just like the Blossoms’, depends on whether one wants to pay with them or treats them as an object of fine craft that they are.

- 1 gold – Seed – Made for larger transactions or decorative purposes, these coins are thicker and pentagonal in shape. Usually, they are inscribed with some text – commonly the name of the month or other events contemporary to when they were minted.

More than immersion!

As you can see, that’s not just a name convention for enhanced immersion anymore. It’s a potent worldbuilding tool!

Elune’s light upon you!

I did the same with calendar names some time ago, when I ran a campaign set in the world of Azeroth (the world of “Warcraft”). Since the action was taking place in Kalimdor’s dry, savannah-like Barrens, I made up the month names fit for such a climate. All months were named as “Moons” (since both Night Elves and Tauren worship the moon in a way), with a one-word descriptor to reflect the season (wet or dry). It went like this:

- Cleansed Moon

- Cold Moon

- Windswept Moon

- Swelling Moon

- Sunken Moon

- Murky Moon

- Sprouting Moon

- Parched Moon

- Thirsty Moon

- Scorched Moon

- Languid Moon

- Thundering Moon

I’ve just kept the calendar table on the player-facing side of my GM screen all the time, with a marker on the current (or last checked) date. And though the names themselves didn’t matter much, the flow of time was visible. Moreover, I could use that to foreshadow some events in the campaign, like storms hitting in the late months, which were connected to the campaign’s plot.

Also, the weeks were aligned with the moon phases, so the nighttime visibility (another thing coming in the gameplay a lot) was easy to intuit for the players.

You can do that in the Forbidden Lands, too!

So, with my description of different currencies above, you can easily hint at some backstory information. You can make your players guess what was the history of a ruin they’re plundering. And that’s true whether you carefully crafted an adventure site yourself or you just rolled one on the GMG tables! Pre-Blood Mist Alderlander ones could contain snake-themed coins, while those established during the reign of the Rust Brotherhood will have almost exclusively the other set. You can make a thing about the “heretic” coins, when some Rust Brothers will refuse – or even forbid – the use of the currency bearing the symbols of Wyrm. At the same time, some old elvish or dwarven coins can provide questions. And the potential for puzzles and riddles here is vast, too!

Let me know how you liked it! And what are your additions to the setting’s material? What else helps you ground your players in your game’s world?